I tend to run Ubuntu on my computers as the primary operating system. Given I work for Canonical, this isn’t especially surprising. However I have run Ubuntu on pretty much everything since 2005 or so - long before I started working at Canonical (in 2011). Mostly I will upgrade as each new release comes out, only doing a clean install once in a while.

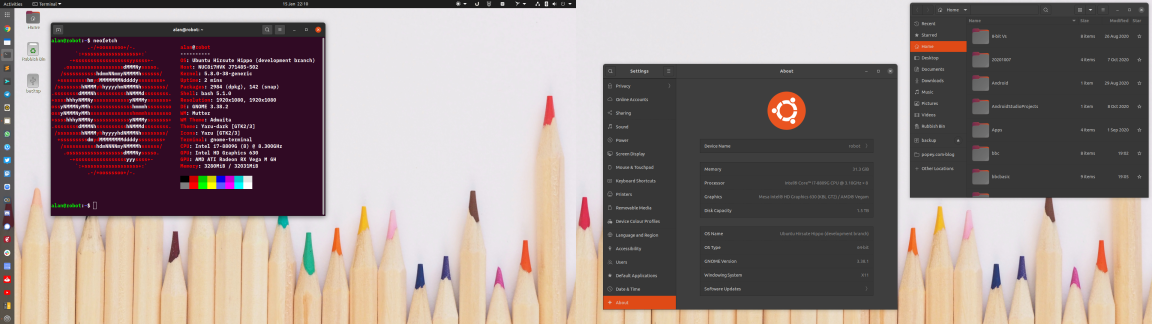

I ran GNOME 2 for all the years from 2004 through to Unity being released, then switched to that. After Ubuntu switched from Unity to GNOME Shell I went along with that in late 2017, and have mostly been running it ever since. I sometimes run other distros in VMs, or play with live environments, but I tend to stick to Ubuntu. Not for any company imposed reason - there’s a bunch of people at Canonical who run Arch, MacOS or something else. I just prefer Ubuntu.

Every so often I’ll have a dally with another distro, but usually return to stock Ubuntu at some point. Back in February 2018 I was flying back from a company event in Seattle and decided on a whim to nuke-and-pave my ThinkPad T450, replacing the OS with KDE Neon. I hadn’t used KDE for a long while, so thought I might give it a whirl.

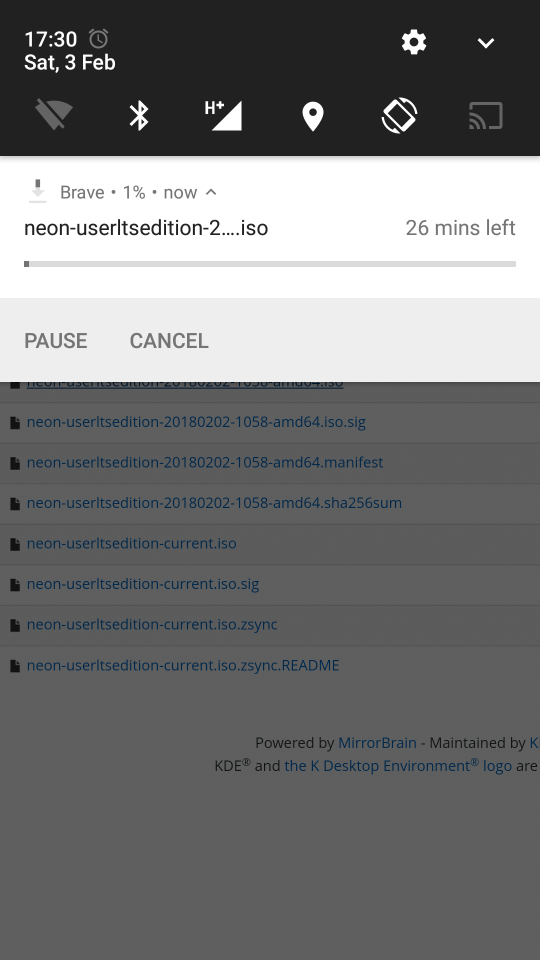

Unfortunately I made this decision rather late in the trip, as I was waiting at the gate to board the plane home. I made the decision to install the OS while flying home, offline, in flight. I started trying to download the KDE Neon ISO image over airport WiFi while running out of time before boarding started. As I had international roaming on my cellphone, I switched to that.

It takes an unsurprisingly long time to download a 1.6GiB ISO image over HSDPA+! I wasn’t sure it would complete in time before we boarded. Martin captured the stressful feeling while we sat at the gate.

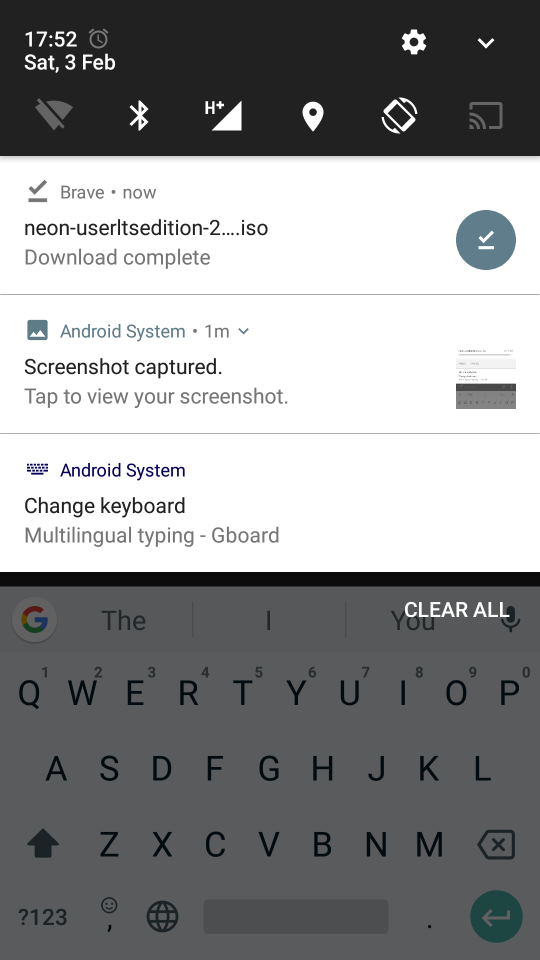

However, 22 minutes later..

Then came the fun of trying to get an ISO image off the phone, and onto a USB stick to subsequently boot on my ThinkPad and wipe it. Thankfully Martin had a spare USB stick handy, and with a little wine-fuelled (the drink not the not-an-emulator) shenanigans, we got it working. Martin kindly took a quick snap of me post-install.

Here's @popey installing @KdeNeon at 30,000 feet. See how excited he looks. How did it turn out? pic.twitter.com/jWVrdR6kPp

— Martin 🙂 Wimpress (@m_wimpress) February 4, 2018

I stuck with KDE Neon until August 2019 when I switched back to Ubuntu. I covered it in this twitter thread. No drama, I just chose to switch OS back to Ubuntu. KDE Neon is excellent, and maybe I’ll use KDE again some day. But for now I’m back on Ubuntu proper.

As before, I tend to upgrade every six months, when a new release of Ubuntu is out. I prefer to use the upgrade tools do-release-upgrade and update-manager but sometimes I’ll go off-piste and do a “manual” upgrade. Generally it’s best practice to use the aforementioned tools to upgrade Ubuntu. They’re coded to cater for “quirks” which attempt to ensure a reliable upgrade from one relase to the next.

I know some people are very much of the “nuke and pave” type of desktop OS upgrades. Perhaps they’ve been burned by upgrades in the past, don’t trust the process, or like a “clear out” when they upgrade. I’m none of those, and I like to exercise the tools, because most of our users will be using them. Nerds will often suggest that “nobody” does in-place upgrades and “everyone” just clean-installs. They’re very, very wrong.

So I feel it incumbent on those of us who are technically skilled to un-break their system if it does go wrong, to do these upgrades and find the sharp edges so our “normal” users don’t have to. Obviously we can’t find every possible problem that may occur. But we can certainly be the canary in the coal mine, to find at least some of the roughness in the process before releases to the wider community.

Users are very good at doing weird stuff to their systems. Often they’ll add 3rd party repositories to get newer software, or replace critical system components for some reason. Frequently they’ll follow a copy-and-paste-able guide online to overcome some problem, or fulfil a desire, then promptly forget they did it. They may not even understand what they did, just blindly pasting commands into a terminal.

Six months or a year later, when they get a prompt to upgrade to the next Ubuntu release, they won’t remember the commands they ran, which removed some core component, or replaced it with a funky version. When they attempt to upgrade, if it fails, it’s the fault of Ubuntu or Canonical, in their mind. Don’t get me wrong, the upgrade process isn’t perfect, and there’s certainly additional checks and balances which could be added, or quirks, to compensate for a “broken” starting point.

If a user isn’t equipped to understand, debug and fix the issue, or doesn’t have access to another technical person who does, they may get frustrated and wipe the system. They’ll have learned “Upgrades don’t work” and “Nuke and pave is the best way”. If this person actually is a technical expert, and they still can’t fix it, then they may tell their wider network not to upgrade, and always clean-install.

One outcome of this, is that nobody tests upgrades. Everyone is told they don’t work, so they don’t do it. If someone does upgrade, and it works, no complaints are made, nobody counters the “upgrades never work” assertion, and it becomes pervasive de-facto knowledge that “nobody upgrades”. This leads to a downward spiral of fail as nobody has confidence in upgrades, so they don’t test them anymore, and thus the quality diminishes further. I’ve long lamented this.

It makes sense, if you only have one computer, and you need it, that you wouldn’t potentially compromise its usability by trying a major release upgrade, as it might cause a significant outage. Upgrading your primary computer only to be presented with a flashing cursor on a black screen, and if you’re lucky, a login prompt is a horrible experience for anyone.

It’s totally understandable when an upgrade goes bad, if the user doesn’t get an instant answer, they will often wipe the system completely to do a fresh install. What makes this whole thing even worse, is when an upgrade goes bad, there’s logs and other data which could be collated to debug the problem, but the user likely wiped them when they clean-install. That makes it almost impossible to diagnose what went wrong, and prevent it in the future.

I’m lucky that I have more than one computer. So if an upgrade did go catastrophically wrong I could use another PC in the meantime. Not everyone has this luxury though. It would be good if upgrades could be made more robust, or could detect likely error situations before they run. Maybe a pre-flight check which summarises things the user might want to do. I know the upgrade tools already do some of this, but I wonder if there’s more we could do.

I don’t know what the solution to this is (no, switch to a rolling release isn’t it, I’m pretty sure of that), but I’m interested to hear people’s thoughts.

For now though, I just upgraded my desktop to Ubuntu Hirsute Hippo - which will become Ubuntu 21.04 in a few months. I’m now running it on all my systems.