Canonical is planning an ‘All Snap’ desktop next year. It will likely be available side-by-side with the traditional deb-based installation we’ve been used to since 2004.

If the “All Snap” or “immutable” platform is to be a success, Canonical needs to get a grip on the broken, uninstallable, insecure, and outdated snaps provided in the snap store.

This is a long post, so feel free to skip to the ‘Solutions’ section for my positive thoughts.

Featured snaps

The snap store has an “Editor’s Picks” section which is used to promote applications. Featured applications generally get a ton of eyeballs, and thus installs. Many people may be surprised to hear that ’normies’ often use the graphical software storefront to install applications on Ubuntu (and other distros). Not everyone uses apt or synaptic as their software store frontend.

Some of those featured lists aren’t kept up to date much anymore, though. Meaning that some high-profile applications are missing out on promotion. Worse, outdated applications are being promoted.

Security updates

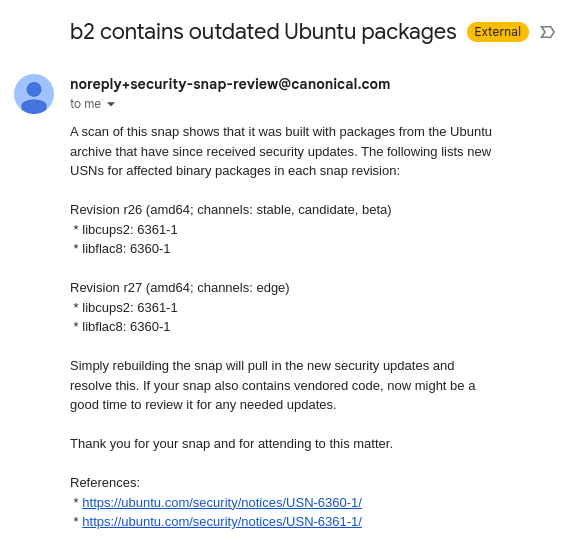

When building a snap, often a developer will need to include debs from the Ubuntu repository inside the package. These utilities and libraries are bundled at snap build time. These dependencies get updated in the repository, for example when security issues are found. As a consumer of those deb packages, developers should rebuild your snaps to include the security updates.

The security team at Canonical have a bot which scans all snaps, identifies when they include debs that have been updated, and urges the publisher to update their snaps.

These emails get ignored, and the security team knows it.

Uninstallable snaps

There are some applications on the “Editor’s Picks” which are not installable.

Some are only installable in specific regions. The Pageme Business snap for example, shows up in Productivity snaps but is uninstallable, unless you’re in South Africa.

It certainly makes some sense to have applications region-locked if the functionality only works in that region. It makes no sense to show them as ‘featured’ to the rest of the world.

Another, creeperx has no stable releases.

Outdated snaps

Around one-hundred and eighty snaps have had no updates in the last year. Some of those are old, perhaps feature-complete applications. A lot of them aren’t. Here’s a sample of ten from the full 180+.

- light-player

- dm-tools

- unscripted

- iheartradio

- express-pos

- bitshares2-light

- vdinar

- cointop

- syscoin-core

- simplebudget

“Command-line tools for the lazy” - dm-tools for example, was last updated in the snap store, in March 2021. It contains a small number of programs written in python. The upstream was last updated in 2022, a year later. It bundles a small number of python dependencies.

This is likely a low-impact example snap, but it does have network connectivity and potentially outdated python modules bundled.

Possibly more worrying is syscoin-core, an “experimental digital currency that enables instant payments to anyone”. Last updated in the store over two years ago. The upstream website suggests a new release (4.4.2) was made this year, but the snap store wasn’t updated.

Really outdated snaps

One year out of date might not be so bad, for an application which isn’t updated often, or is considered feature complete. However there are sixty snaps which haven’t been updated for three years. Here’s a small selection:

There’s twenty-six snaps in the store which haven’t been updated since 2018, and thirty-seven which haven’t had an update since 2017.

How did we get here?

Numbers

There are approximately 6000 snap packages published in the Canonical Snap Store that are publicly available and built for the 64-bit Intel architecture.

alan@nuc:~$ wc -l /var/cache/snapd/names

6003 /var/cache/snapd/names

I’m being intentionally specific in that sentence because there are other non-public snaps, non-public stores, and multiple architectures. Some of these are desktop applications, while many others are command-line utilities, servers, daemons & agents

Many of those snaps are junk though. By ‘junk’, I mean test packages or other things that no end-user would install intentionally.

alan@nuc:~$ grep -v ^test /var/cache/snapd/names | wc -l

5903

This is a byproduct of the design of the snap store. Anyone can sign up, register a unique package name and start uploading. It’s a compelling feature!

Go to the very bottom of this post to the Appendix to see how easy it is to register a name, build a snap and push it to the store.

The store also contains some duplicates. Here’s a small selection.

alan@nuc:~$ grep ^youtube-dl /var/cache/snapd/names | wc -l

5

alan@nuc:~$ grep ^yt-dl /var/cache/snapd/names | wc -l

3

For the purposes of this blog let’s hand-wave that away and say there are somewhere between 5000 and 6000 snap packages published in the Canonical Snap Store. 5000 is a nice round number so let’s use that.

Snap advocacy

Between ~2016 and ~2021 there was an active ‘Snap Advocacy’ team at Canonical. I was on the team along with anywhere between two and six other people. I left in April 2021. I still maintain a few snaps, but I’m guilty of not updating some for a while. So this is a problem which I am invested in being improved.

During our time, we helped maintain a bunch of snaps. Some were under our own names, others were published by the ‘upstream’ developer, and some came under “Snapcrafters”. The advocacy team’s initial goal was to get more applications published in the Snap Store. We were to drive adoption of the packaging format among software developers.

We would promote the snaps on the Snapcraft Blog, Ubuntu Blog and the respective Twitter accounts.

We also gathered feedback from developers on problems they encountered with snaps, and ensure the snap and snapcraft teams were aware, and could prioritise those items appropriately.

Here are some of the strategies we employed over the years.

Lighthouses

We identified a set of lighthouse applications. These were typically high-profile, well-known applications from household names. For example, Spotify, Slack, Discord, VLC, Google Chrome, and other software you probably already have installed somehow.

We’d have calls with the developers or conversations over email, IRC, Slack, or wherever they hung out. We would usually only spend thirty to sixty minutes trying to understand their software production pipeline, and how (and if) snapcraft could be part of that. Some of the developers were looking at ways to simplify their Linux publishing strategy, so we turned up at the right time.

We had so many of these conversations though, and many ended differently. Some just said “Sure, let’s do it”, and we would get those packages built and published. They would integrated the publishing in their pipeline and everyone’s happy.

At the other end of the scale we had developers tell us they were not interested and would refuse to use snapcraft. That allowed us to learn why and feed that back to the team. We never expected to get a 100% success rate.

Others took a lot of time and effort to get over the line. One high profile application took a solid year from first contact to being published and celebrated in the store. At the initial call they said “You have to understand Linux desktop is 1% of my userbase, so you have 1% of my attention”. Phrases like that can be quite grounding when you work on the Linux desktop! We did it though, and the snap is one of the most popular in the store.

Direct contribution

I’m sure every developer loves their own code like a baby, but not every application is a Lighthouse. Some are one-man-band projects with a single overworked developer spinning plates to keep things going.

In those cases, we’d often just contribute directly to their repository with the packaging configuration ready-made. In the pull request we’d explain what the Snap Store was, and how to get pubished. Some developers would investigate further, then accept the configuration, and get published soon after.

That was the best-case scenario though. Often it didn’t work out like that. Sometimes we would have lengthy conversations on their issue tracker about why they might want to do this. In some instances, their own community (or random interested parties) would join in. Sometimes, people would lobby for the developer not to publish a snap. They’d argue with us in someone else’s issue tracker. Often they’d pressure the developer to try Flatpak or AppImage instead.

We would sometimes hold a sprint in the Canonical London office. We would all sit around with a big ‘hit list’ (a spreadsheet) and try to get as many over the line in one day as we could. It was fun and exciting doing this, especially when a developer just said ‘yes’ and took your changes immediately.

No thanks

There were plenty of rejections for numerous reasons. Some projects simply didn’t want to do binary releases, but were happy for distributors to do that for them. Others didn’t have the time to take on more packaging and the maintenance it required. Some (very few) were anti Canonical, or anti snap.

Snapcrafters

We identified a significant number of decently high profile applications and utilities, where the upstream didn’t want to maintain them. We knew these would be popular with users, so we elected to publish them ourselves. The Snapcrafters community was born on GitHub.

The mission was to publish and keep updated a set of applications, much like any existing Linux distribution does, but as snaps. This is comparable to the way Flathub has a set of repositories for publishing community-maintained applications. The difference being for Flathub this is the primary way of publishing, whereas for the Snap Store, this is an alternative, secondary option.

Individual publishing

Some of us on the team, and in the wider community committed to packaging applications as individuals. This was especially the case if we personally used a package, and wanted it to be kept up to date.

I personally have nearly one hundred snap names registered on my account. Some of those are just test or prototype snaps I worked on, and never published. Others are public, working applications that are relatively up-to-date.

Some are just broken, and likely won’t get updated any time soon. Perhaps the upstream project made a change which I didn’t keep up with, or the snapcraft configuration no longer works.

I certainly overcommitted to a bunch of snaps, which I just can’t keep up with. So about a year ago, I posted on the snapcraft forum, asking for help. Some of the applications were adopted by other developers. Others are still on my plate.

I did update a few last weekend. The b2, x16-emu, Azimuth, ClassiCube, Session Desktop, sfxr and more, all got updates. I made some ‘private’ so they aren’t installable anymore because I just don’t have the time to unbreak all the broken ones.

I don’t think I’m alone with this. There are plenty of other snaps in the store that need some attention.

Where we are

As I mentioned, there’s around five thousand snaps in the store. Hundreds of them haven’t been touched in years. Some developers have just abandoned their packages.

Of course people move on from projects all the time, and sometimes just drop old software on the floor. That happens. With traditional Linux distribution repositories, there’s a community to maintain those applications. The Debian developers maintain packages in their archive. The Ubuntu “MOTU” maintain their packages. While there’s guard rails on who can promote packages in the archives, anyone can contribute updated packaging to software in the repositories.

That’s not the case for snaps. There’s no guarantee that the packaging information is publicly hosted. The snap could have been built and uploaded from a developer workstation, or from inside a private git repository. If the packaging is updated by an eager community member though, only the publisher can push an update to the stable channel. Nobody at Canonical is going to jump in and nudge a package forward in the snap store. That’s down to the publisher, by design.

If they walk away, packages are effectively orphaned. There’s likely hundreds of orphaned packages in the snap store right now.

Maintaining snap packages is hard. If your software is baked in aspic with no library updates and no other intrusive changes, maybe your snapcraft.yaml can stay the same, with minimal hand-holding to update it. But modern software changes. Developers want to use the latest libraries and frameworks. If your libraries are only available or only function on a newer LTS of Ubuntu, then it’s more painful to change the snapcraft.yaml.

Moving a snap from core18 to core20 and core22 is a frustrating experience. The confined audio subsystem breaks, and the graphics stack breaks. You might find your application works on a machine with an nVidia GPU, but not on one with an AMD GPU. These issues shouldn’t happen now we’re on the fourth iteration of core since snapcraft started.

Sometimes developers get stuck, unable to resolve snapcraft packaging issues. Packaging software in a relocatable, containerised format isn’t always easy, that’s for sure. The main support avenue for snapcraft issues is the forum. Recently one developer “ragequit” citing a lack of support as one reason.

Solutions

I want to see this situation improve. In general, Canonical should incentivise the promotion of applications and dis-incentivise letting applications languish.

Specifically, Canonical could:

- Remove applications from the ‘Featured’ category which have no stable releases

- Prevent users from seeing geo-locked applications from other regions altogether, or remove those applications from the featured groups

- Be more forceful when snaps have outdated deb packages inside

- Place a ‘call to action’ in the security report emails. Perhaps link directly to the snapcraft build site (for those that use it)

- Make the emails public on a site like https://ubuntu.com/security/notices so users can see which snaps need updating

- Highlight to users in the storefront when a snap contains outdated debs that contain known CVEs

- Place a banner across snap store pages highlighting very old applications

The goal in all of this is to make sure users are informed when things are outdated, and developers are encouraged to update their stuff. I’m just as guilty of letting things get outdated, so I need a nudge too.

I’m keen to see the new all-snap Ubuntu Desktop when it lands next year. But my biggest worry is the experience users will get installing broken, outdated, insecure packages on their shiny new system.

Canonical has six months to turn this around. I have faith in them.

Appendix

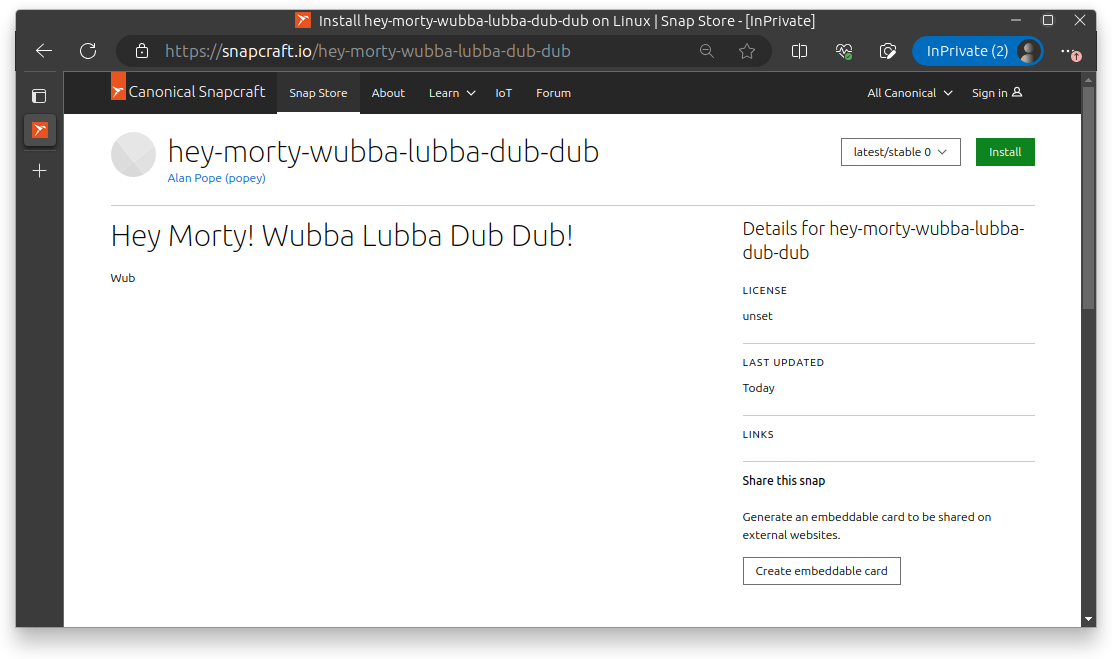

As mentioned above, it’s trivial to register a snap, so it’s not surprising there’s a high number of ’test’ snaps.

Let’s see how easy it is to register a name and publish in the store. I already have an account and am logged in with snapcraft (the utility for building snaps).

alan@nuc:~$ snapcraft whoami

email: [email protected]

username: popey

id: [redacted]

permissions: package_access, package_manage, package_metrics, package_push, package_register, package_release, package_update

channels: no restrictions

expires: 2024-09-15T10:55:49.000Z

Let’s pick a unique app name:

alan@nuc:~$ snapcraft register hey-morty-wubba-lubba-dub-dub

We always want to ensure that users get the software they expect

for a particular name.

If needed, we will rename snaps to ensure that a particular name

reflects the software most widely expected by our community.

For example, most people would expect 'thunderbird' to be published by

Mozilla. They would also expect to be able to get other snaps of

Thunderbird as '$username-thunderbird'.

Would you say that MOST users will expect 'hey-morty-wubba-lubba-dub-dub' to come from

you, and be the software you intend to publish there? [y/N]: y

Registered 'hey-morty-wubba-lubba-dub-dub'

Now we “build” the app:

alan@nuc:~$ mkdir -p hey-morty-wubba-lubba-dub-dub/bin

alan@nuc:~$ echo $'#!/bin/bash' > hey-morty-wubba-lubba-dub-dub/bin/wub

alan@nuc:~$ echo "echo Hey Morty. Wubba Lubba Dub Dub" >> hey-morty-wubba-lubba-dub-dub/bin/wub

alan@nuc:~$ chmod +x hey-morty-wubba-lubba-dub-dub/bin/wub

Next we make the snap metadata:

alan@nuc:~$ mkdir hey-morty-wubba-lubba-dub-dub/meta

alan@nuc:~$ cat > hey-morty-wubba-lubba-dub-dub/meta/snap.yaml << EOF

name: "hey-morty-wubba-lubba-dub-dub"

summary: "Hey Morty! Wubba Lubba Dub Dub!"

description: "Wub"

confinement: strict

grade: stable

version: "0"

apps:

"hey-morty-wubba-lubba-dub-dub":

command: bin/wub

EOF

Let’s build our snap:

alan@nuc:~$ snap pack hey-morty-wubba-lubba-dub-dub/

built: hey-morty-wubba-lubba-dub-dub_0_all.snap

QA time!

alan@nuc:~$ snap install ./hey-morty-wubba-lubba-dub-dub_0_all.snap --dangerous

hey-morty-wubba-lubba-dub-dub 0 installed

alan@nuc:~$ snap run hey-morty-wubba-lubba-dub-dub

Hey Morty. Wubba Lubba Dub Dub

Ship it!

alan@nuc:~$ snapcraft upload ./hey-morty-wubba-lubba-dub-dub_0_all.snap

Revision 1 created for 'hey-morty-wubba-lubba-dub-dub'

alan@nuc:~$ snapcraft release hey-morty-wubba-lubba-dub-dub 1 stable

Released 'hey-morty-wubba-lubba-dub-dub' revision 1 to channels: 'stable'

Done.

You get the idea.