Lies

Neither of these are “App Stores” in the way average people know them. You can neither buy or sell products in these so-called ‘stores’…

…yet.

The wording on those two screenshots above is both hilarious and sad. It’s very reminiscent of People’s Front of Judea or Slim Shady.

Anyway, here follows a bit of a moan about all this (the app stores, not Monty Python or Eminem).

Background

I have previously lamented on the following subject as a stream of tweets. The topic has been on mind mind again recently though. So I thought I’d revisit and expand my thoughts.

When I see macOS developers like Steve publishing applications like this, it makes me sad. Don't get me wrong, I'm happy for him. It looks like a cool and useful application, that he's put some effort into. I'm sad because we don't have this on #Linux ..https://t.co/L0jOj0nwFL

— Alan Pope (@popey) June 3, 2021

Scarlet

That tweet of mine linked to one from Steve Troughton Smith, who has subsequently deleted his Twitter account. Thankfully, the Internet Archive have captured it here. In short, Steve was announcing a small MacOS application he’d recently developed, called Scarlet, an “Issue tracker and task manager”.

My original thread wasn’t really about Steve’s application - I’ve never tried it, but I’m sure it’s great. The thread was more just me lamenting the fact that in mid-2021, there was no easy way to sell (or indeed buy) desktop applications on Linux.

Callsheet

What recently got me thinking about the topic again was a conversation on episode 547 of Accidental Tech Podcast (an Apple-centric podcast). In it, the presenters discussed (at length) publishing an app for MacOS called Callsheet. Written by Casey, a presenter of ATP, Callsheet is essentially a nicer way to look up films and TV than IMDB.

One part of the conversation was about app pricing, specifically subscriptions vs outright payments. The team have discussed this topic more in previous episodes. Each time they do, I’m reminded (again) that these capabilities on MacOS and iOS still aren’t easily accessible (yet?) on desktop Linux.

Subscriptions

There has, of course, been a significant change in the way software is funded over the last decade. It’s far less common to buy a boxed or downloaded copy of software at a one-off price, outright. More typical is to subscribe to services via the application.

Whether that’s a Spotify music subscription, Slack sub for keeping your chat history or Google Drive for storage, they all use ‘The first hit is free’ hooks, and are subscription-based.

That said, there are still plenty of pay-once applications on other platforms, but they’re less common than they were.

Games

There’s also the games category, which I’m not going to cover here, because that’s a whole other kettle of fish, and is well served on all platforms, for paying outright, subscription and in-app purchases.

On Linux

To be clear, I’m not complaining that we don’t have these aforementioned applications on the Linux desktop. That’s not the point. The point is “we” still don’t have a robust way for developers to monetise their application development work.

Most desktop Linux users run Ubuntu. Followed by others you’ve likely heard of like Arch, Fedora, Manjaro, SUSE and friends. Most users of these desktop Linux distributions have no baked-in way to buy software.

Similarly developers have no built-in route to market their wares to Linux desktop users. Having a capability to easily charge users to access software is a compelling argument to develop and market applications.

Some options do exist

There certainly are ways and means to generate some revenue from users of a Linux distribution, of course.

Elementary App Center

One Linux distribution - elementary OS, stands out from the rest as embracing financial support for developers. They have a bespoke “App Center” for their native Open Source applications. This enables users to show support to developers of elementary OS applications via optional payments. They can also choose not to contribute financially, and still get the software.

However, the vast majority (by some margin) of desktop Linux users (of which there are millions) do not run elementary. Some do, most don’t. So an application developer targetting elementary OS is unlikely to make a living wage or successful business from voluntary contributions.

Donationware

Other Linux distributions offer the ability for users to donate using third party websites, to support development. Linux Mint, Solus and Ubuntu MATE are good examples. They use tools like OpenCollective, Patreon and PayPal to collect funds.

In general though, these funds are for the development of the distribution as a whole. The administrators of the distribution allocates the collected funds to services and developers which support the maintenance of the distribitions and applications they ship.

Those funds may or may not go to applications that users feel are needing financial recompense. It’s not a direct user to developer relationship, the distribution sits in the middle.

If a user wants to reward a specific developer, or an independent developer wishes to get paid a living wage directly for app-dev work, the above models generally don’t work.

Indie devs do exist

Sindre Sorhus is a prolific developer of mostly free applications.

Sindre is an example of an individual full-time Open Source developer who is able to fund their work via voluntary sponsors. With (at the time of writing) seven $1000 sponsors, five $100 supporters, nine $50 contributors, and many more $10 patrons, Sindre could be considered a success story. But that’s one person.

While those applications are native to MacOS, there are some examples of cross-platform applications they’ve developed which are published for Linux, such as Caprine. I built and published the Caprine snap when I worked at Canonical some years back, and handed it over to Sindre.

My point being, it is possible for a developer to carve out a successful niche developing and publishing predominantly free applications for other platforms. Why not desktop Linux?

Host your own

It is totally possible for an individual developer to stand-up a web store and sell digital download applications. Indeed there are plenty of those. The problem these have is discoverability.

The average desktop user is very similar to the average mobile user - dare I say - they’re the same human beings!? They are used to the concept of App Stores like those on iOS and Android. Having your paid application in an app store grants it exposure to eyeballs who wouldn’t ordinarily have stumbled on a random webstore.

Prior attempts

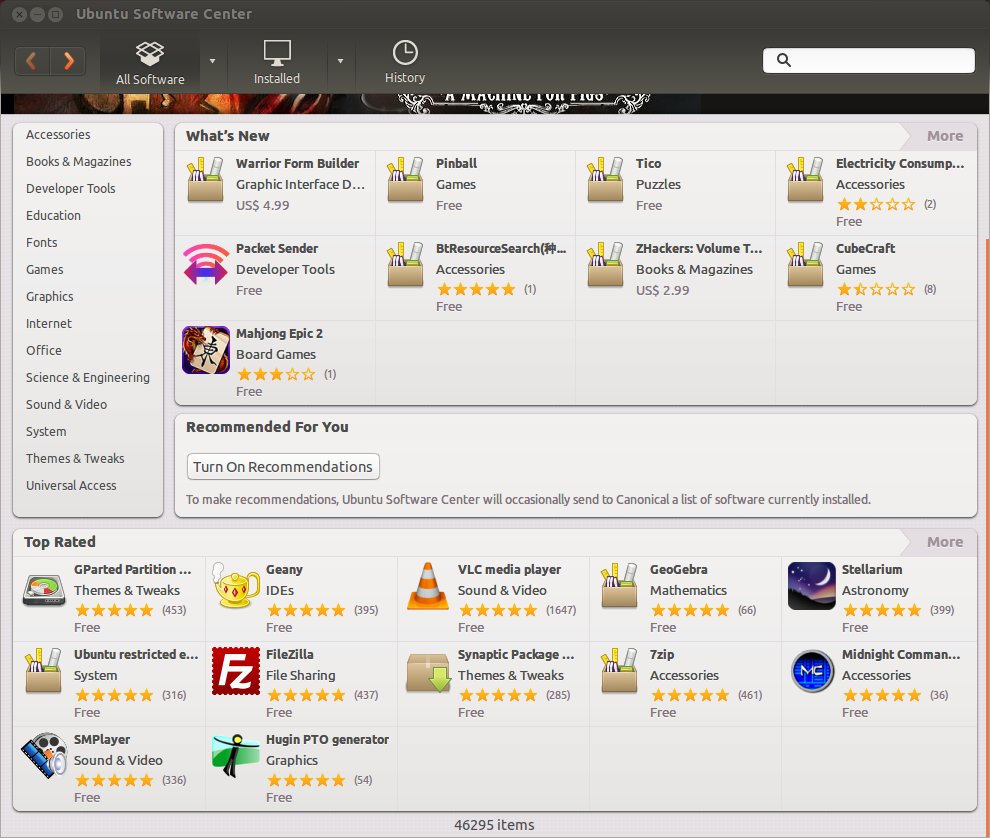

Ubuntu alone has made multiple attempts in the past to enable paid applications via a built-in storefront.

Ubuntu Software Center Centre

If you ran Ubuntu on your desktop back in 2012/2013 you would have been able to buy paid apps via Ubuntu Software Centre. Third-party application developers could (and did) package their software as a deb and publish for Ubuntu users. Only users who paid for the app were able to download the applications.

There were no in-app purchases, no donations, and no subscriptions. You paid once, then you get the app and updates from a special, private PPA.

This failed for many reasons. The debs are notoriously difficult for non-Debian people to make and maintain. If you’re an application developer using Qt, or an indie game dev using Unity, Debian packaging is likely a dark art that you don’t want to learn.

Note: Whenever I say the above, an experienced Debian Developer will almost always pop-up and explain it’s not that hard, anyone can learn it, here’s the packaging guide. Don’t listen to them, they’re wrong.

The ARB (Application Review Board)

Canonical tasked a team called the ARB (Application Review Board) - actual humans - to help developers get their application published. This often required many round-trips between the ARB and the developer to make a standards-compliant Debian package. Eventually the developer could publish their application. But this iterative and gated process was required for each release of the application.

The process was slow, labourious, and painful for the publisher. For the ARB, there was a constant firehose of pending applications. Doing ARB review activites wasn’t even their primary role in Canonical. This was additional work on top of their existing tasks.

Pricing

The minimum price point for applications was too damn high. A developer couldn’t set the price of their application to 99¢ because the minimum was ~$5. For a small application or utility, in 2012, on a fledgeling store, this pricing inflexibility was an unreasonable ask.

Developers would put in a ton of effort to make and maintain a deb, suffer many round trips with the ARB to review it, then to have almost nobody buy their application because of the price.

Reception

Some developers did persevere, but the sales were disappointing. So it just wasn’t worth the developer time to publish there.

Eventually the number of reviewers on the ARB dropped off, and the lists of requests for packaging became very long. Canonical pretty much gave up on this as it just wasn’t profitable.

Humble Bundle

While it was painful for individual developers to get their applications published, larger organisations had less of a challenge. Canonical would often task developers to package up software on behalf of the external partner. While similar to the indie developer experience, in this case, typically all the packaging work was done by Canonical developers to completion.

One example partner was Humble Indie Bundle. In the early ‘Indie’ days (the single digit bundle numbers), Canonical would publish the Humble Indie Bundles in the USC (Ubuntu Software Centre) simultaneously with them going live on the bundle site itself.

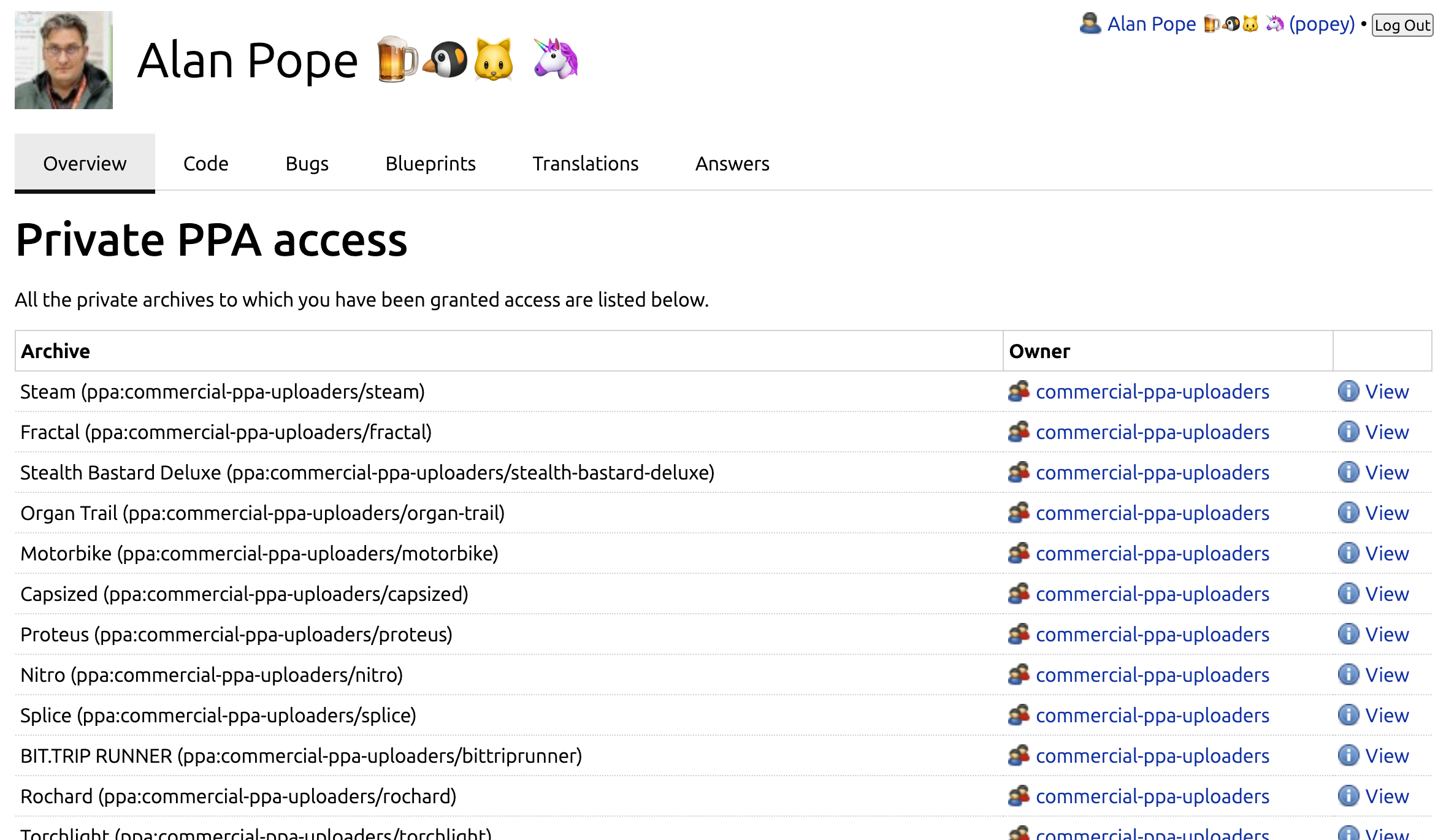

Just like ARB-published debs, these were made available via private PPAs on Launchpad. Even now, over a decade later, my private PPA subscriptions are all still there, with old builds of those games, sitting there waiting.

This enabled users to install the games/applications directly from their desktop without having to download random binaries from a third party website. It also helped bolster the reputation of USC, leveraging the goodwill that Humble Indie Bundle had at the time.

Ubuntu Phone diversion

In 2013 Canonical publicly dived head-first into the Ubuntu Phone project. It was mostly privately developed internally up until then. The ultimate goal was to deliver a converged user experience, simplified application development process and of course, phones, tablets, TVs and laptops running Ubuntu Touch.

Ubuntu Touch used click packages which were somewhat eaiser to build than Debian packages of the past. The Click Store also enabled payments for applications. Not many apps turned on payments though. There was a paid Reddit app, and a couple of games. The minimum price per application was $2.99.

There weren’t enough devices sold, and 3rd party application developers couldn’t be convinced to port their applications to Qt/QML for the devices that were sold.

New packaging formats

Snapcraft

With Snapcraft and Flathub the package maintenance and publishing process has been smoothed tremendously. But as far as I am aware, neither of them has the ability to do IAP (In App Purchase), like Steve has at the top of this blog, or paid purchase of published applications.

The snap packaging format ’evolved’ from click packages in the Ubuntu Phone project. Unfortunately the payment system used by the Click Store was not brought across to the Snap Store. Snap does have some of the features needed (run snap buy for example). But the whole end-to-end process isn’t there (yet).

The Flathub developers have had plans for delivering paid applications in 2023. Perhaps they’ll beat snapcraft to the punch by the end of this year?

Not yet

I would love to be able to publish little applications like Steve’s in a storefront for Linux users. Also, as a user, I’d want to pay for the hard work of others in as simple a way as I do on my Android phone, or via Itch or Steam. But I can’t, yet.

For sure, I can (and do) throw money at a patreon, paypal, ko-fi or buy a developer some coffee, beer or something from their Amazon wishlist. But I can’t just click “Buy” and “Install” on an app in a store on my Linux laptop.

Maybe one day all the ducks will be in a row, and I’ll be able to buy applications published for Linux, directly on my desktop. Until then, I’ll just keep looking longingly at those macOS app developers, and hoping.

Appendix

Please find below some phrases you, or someone close to you may have shouted while reading this article, along with my response.

“What about AppImage!?”

Whenever someone mentions only two of the horsemen of the packaging apocalypse, someone always brings up the third, AppImage. Well, fun theory, it’s probably likely there are more paid AppImages in the world than all the paid snaps and flatpaks put together.

I know I’ve bought software which has been delivered in an AppImage before now. Unfortunately not from an App Store, which is the point of this article.

If we’re being pedantic, I’ve actually also paid for a snap. Back when I worked at Canonical, I tested the fledgeling snap buy command, and made a video showing how terrible the process was. That project was immediately cancelled/postponed. I hope it comes back some day! It’s quite neat to snap buy something on the command line.

“We don’t need your sinking proprietary apps!?”

You might not, but the great unwashed do.

Also, you’re objectively wrong. The vast majority of applications downloaded from the snap store and flathub are either proprietary (Chrome, Steam, Discord, Slack, Spotify, Microsoft Edge, VS Code), or are gateways to proprietary software (Steam, RetroArch).

Also, also, I never said anything about licenses.

“Nobody pays for apps on Linux!”

Maybe back in your day, boomer.

This is a terrible cyclic argument. You can’t do that thing, so nobody does that thing, so therefore stats shows nobody does that thing. Therefore nobody should work on it because stats show nobody does that thing.

It’s a self-fulfilly cyclic downwards spiral of nonsense. We need to break out of it. Ideally with both Flathub and snapcraft enabling paid apps within 24 hours of eachother, just to set the cat among the pigeons.